It is commonplace to sees scenes of children role-playing in an early childhood setting. Children create scenes of danger and delight at will, as naturally as breathing.

For instance, in the following two images of children in a early childhood program I ran in 2002, they’re playing with a frequently used prop of coloured material to define a storytelling space.

Images 1 & 2: Preschoolers enacting stories using colour cloth of varying textures and sizes.

Children use the cloth both as costumes and settings. The stories set in rivers and high in the sky are enacted. Sometimes the children take on a storyteller-like voice and other times they tell the story in mime, ideas revealed in pure movement.

Most of the time, the colour of the material is used literally, blue is water or sky and red is fire or the hot sun. Occasionally, the texture of the cloth parallels a quality of the persona being enacted. The children’s movement in the space organises the fictional world, and more often that not, the children remain absorbed in their own narrative event. Nonetheless, I organise the space so that they might also play with being part of an audience. It’s a very dynamic experiment as the children verbally respond to elements of the story.

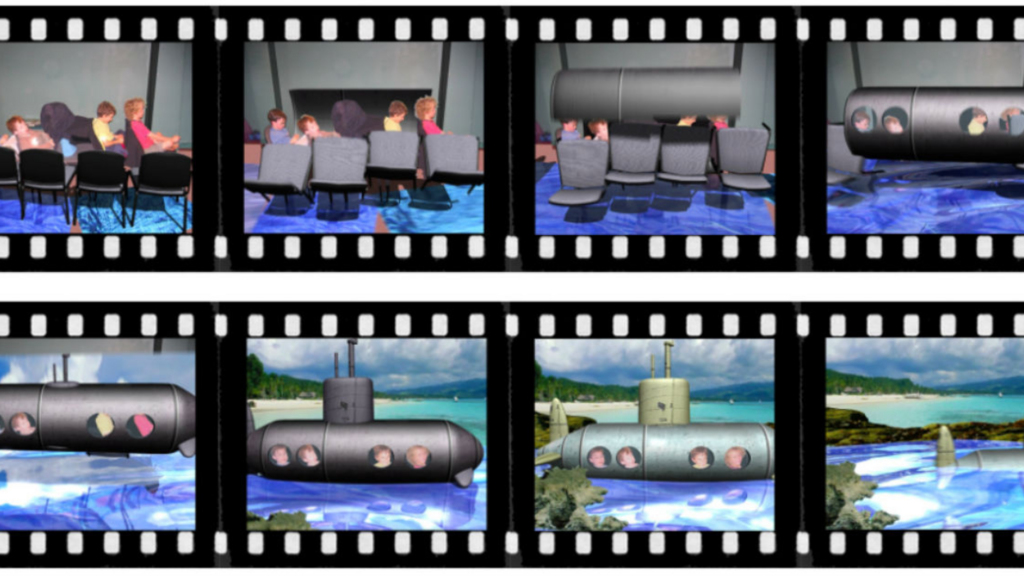

In the third image of four more children in the same early childhood programme, the four pre-schoolers are sitting on four chairs pretending to be under the sea. This time I work with an animator who listens to their story and depicts chairs taking on a life of their own, changing through movement into a tubular submarine.

Image 3: Four pre-schoolers playing make-believe on four chairs.

In the dynamics of the group, I observe whose idea it was to first name the underwater world setting. I then continue to watch who the children believe they are as they go under water. I listen to how the story is woven together (or not) by the four voices as they simply sit on the chairs and declare what actions are taking place. I notice when the story begins to fade out and lose its interest for them. I see that the time to end ‘the play’ has to be negotiated between them, when someone wants to stay with the action and others want to leave. And I watch how the children’s storytelling is extended by the animator’s visualisation of how the chairs can be transformed into a tubular submarine.

Giving more value to role-playing

At the time of taking these images, I am also working on a postdoctoral project with Dr Felicity Haynes at the University of WA, focusing on how arts projects contribute to creative thinking. Through it, I’m gaining a new awareness of the cognitive and social importance of dramatic play through Dr Haynes’ referencing works by cognitive linguists and philosophers on the importance of metaphor to human thinking. George Lakoff’s and Mark Johnson’s Metaphors We Live By and Philosophy In The Flesh uses embodied cognition as the basis of their ‘Conceptual Metaphor Theory’. As the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy noted in 2015,

Embodied cognitive science encompasses a loose-knit family of research programs in the cognitive sciences that often share a commitment to critiquing and even replacing traditional approaches to cognition and cognitive processing. Empirical research on embodied cognition has exploded in the past 10 years.

Consequently, I began to investigate research by theatre and dance historians such as Professor Bruce McConachie on what would later be termed the ‘cognitive turn’ in the performing arts. For instance, McConachie’s Performance and Cognition: Theatre Studies and the Cognitive Turn (with F. Elizabeth Hart) in 2006 was the first of many works on the evolutionary and cognitive basis of theatre and performance studies. Other works included Engaging Audiences: A Cognitive Approach to Spectating in the Theatre (2008), Theatre & Mind (2013), and Evolution, Cognition, and Performance (2015).

Questions which challenged me at the time included how cognitive science might impact on the informal playfulness of the activities for children. On the other hand, I valued how its source of new knowledge offered me useful ways of effectively facilitating role play in my teaching programmes.

A time like never before?

Moving forward 23 years, and I am living in Melbourne and, after retiring from full-time teaching, I’m working as a volunteer for the Curriculum Writers Association Australia. I put my hand up to tackle the implications of AI for planning, delivering and assessing curriculum at the classroom level by presenting online discussions on “What Might The AI-Assisted Classroom Look Like?” Like millions of other teachers, I get that AI is a ‘thinking machine’ and qualifiedly different to previous technologies, so I decide to immerse myself in using it to address the pedagogical issues I noticed were beginning to be address about AI in education. I choose the issues that meant the most to my classroom practice, such as:

- How might I use AI together with mandated learning progressions to create rubrics to differentiate, scaffold and assess students?

- How do I ensure that my students understand and use metacognitive thinking practices to avoid the risks of using AI in ‘metacognitively lazy’ ways?

- How might I use AI to auditing units of work and analyse qualitative data to inform how I differentiate learning tasks, improving student motivation and well-being ?

- How can AI help me better use peer and self-assessment strategies so that students internalise standards and efficacious learning behaviours?

- How do AI apps support and model a learning community ethos in which teachers and students share their love of learning?

Undoubtedly, these subjects are impossibly complex. Nonetheless I pressed on, interrogating how they applied to my teaching of K-12 Drama, K-10 English, and K-8 History. I remained particular cognisant of my years of experience of delivering teaching and learning through dramatic play, alongside my use of Philosophy in the Classroom methodologies. My classroom practice had lead me to contracted to write six textbooks in drama education and one textbook in primary arts-based learning between 1999 and 2010.

However, today was a new day! I no longer felt the need to prove the efficacy of arts in the curriculum but to ask how I was facilitating the analytic and creative processes in the subjects I taught to enhance my students’ Critical and Creative Thinking Capabilities. Like never before, along with Learning How To Learn strategies in general, a student’s thinking capabilities were being identified as the most significant way of counteracting inappropriate use of AI in education. The evidence was reported almost on a daily basis by neuroscientists such as Barbara Oakley and Terrence Sejnowski warning teachers of letting AI ‘doing the thinking for you’. Though nothing about neuroscience is easy to summarise, the problem centre arresting the development of our working memory, which was required to build schema for enhancing declarative and procedural knowledge. Without such schema we have little ability to make use of the deep understanding and original insights that arise from our long term memory.

I’m looking at my cluttered desk, ready to move on.

Like so many teachers right now, I’m coming to terms with the AI-in-education-juggernaut. Yet, at the same time I understand that in the five decades I’ve been in education, we have had continual technological change thrust upon us that has impacted the valuable time we’ve spent with students and colleagues. Ironically, the knowledge that those relationships have been the singular most important reason why I have loved working as a teacher makes the creation of this portfolio website a way of staying focused ‘on the main game’ which starts for me in the deep truths of not only how I teach, but how I learn. For that reason, I am returning to consider the importance of role play in the next series of blogs to consider awesome issues around

- Why pretend play in childhood serves as a foundational cognitive incubator,

- What is known about how role play was evolutionary adaptation that formed the foundation for our complex human cognition,

- How the embodied nature of role play directly shapes our thoughts, emotions, and perception,

- Role play as a critical for developing empathy, and

- What neuroscience shows on how role play enhances our memories.

And just in case you might believe that I intend to depart from considering how these issues impact teaching and learning experiences, I look forward to discussing them in the context of two units of work, a Year 3 program based around Leo Tolstoy’s Three Questions and a Year 10 program entitled “First Audiences” because it is based on an alternative origins of European theatre in Australia which has traditional begun with the 4th June 1789 account of convicts staging The Recruiting Officer for the occasion of the King’s birthday. I have devised the Year 10 study around how Europeans were invited by First Nations people around the Australian continent to view corroborees. The program looks to the representation of those first cultural perceptions as possible acts of reconciliation.

Look forward to sharing my work with you.