I’m clear about the feeling in my Year 7 ‘comprehension transition’ group of 12 students as they repeatedly ask me, ‘Are we the dumb group? ‘ Is that why we have to practice sounding things out?’ This complaint alternates with, ‘This looks like ‘baby stuff’!’

As a literacy team, we have devised some good answers, sincerely expressed, so I say,

This has nothing to do with you not being smart. You’re learning skills that can be learned really well with practice. Sometimes we miss out learning skills along the way in our schooling. [I then tell them about learning the sounds when I went to school only speaking Italian.]

Yet, their words trouble me. I am committed to explicitly teaching the full scope of phonemes, but I see my students battling shame. This makes me reconsider my drama-teaching background. I know I can use drama practices to deal with these emotional issues head-on, and ironically, that has always involved exploring the links between drama and literacy skills. As Professor Joanne O’Mara noted in a 2003 article, I have long been part of exploring how to frame drama as a pedagogical tool for non-drama subjects (p.15).

A History of Linking Drama and Literacy

For years, educators have explored the powerful connection between drama and literacy. An influential text, Beyond the Script (1997), was published by the Primary English Teachers Association (PETA), which helped its ideas reach a broad audience. In the following years, researchers published many articles connecting drama to literacy, learning, and new technologies.

One of the most comprehensive examples is Robyn Ewing’s School Drama™ program, a partnership with the University of Sydney and Sydney Theatre Company. In 2018, Ewing explained how the program used Vygotsky’s social-constructivist theory. It harnessed dramatic play with literary texts to help students co-construct knowledge with peers, teachers, and teaching artists. This created a “collective zone of proximal development” where students used the fictional spaces of literature to build on what they know and explore their world.

A New Era: The Rise of Structured Literacy

However, the educational landscape has changed significantly since those earlier explorations. The “literacy wars” addressed the failures of the “whole language” approach by embracing systematic synthetic phonics (SSP), within a “structured literacy” approach.

Ironically, I found myself on a school literacy team implementing this exact approach. We used Carol A. Christensen’s Reading LINKS SSP program, which focuses on the explicit teaching of oral language. This forced me to consciously examine the historical similarities and differences between the “drama and literacy” approach and “whole language.”

My professional development under literacy leaders Clara Tran and Glenn Hartney from 2022 to 2025 was some of the most prescriptive learning of my career. They modelled the steps for teaching phonics with Christensen’s Reading LINKS. They also challenged me to learn the “KEY comprehension series,” a methodology from New Zealand that teaches reorganisation, inference, and evaluation. Tran and Hartney’s weekly “Reading Labs” and other activities created a rich learning environment that demanded constant monitoring of student achievement.

Applying a SSP approach

This SSP literacy approach taught me that reading requires the coordinated execution of many complex skills. The Reading LINK program showed me that achieving high levels of literate competence involves many interlinking “shifts, concepts and understandings.” For instance, Christensen’s program explains how students master short vowels before moving to long vowels with a silent ‘e’, and then progress to long vowels (single and diphthongs) and other letter-sound correspondences. Learning this made me aware of how I had previously failed to help students understand and practice to become phonologically aware.

It was transformative to see how my students could achieve evaluation once they competently used the skills of reorganisation and inference. These skills require many hours of practice in “reading between and beyond” the lines. The past two years on this literacy team gave me a deep appreciation for explicitly addressing phonological awareness. It is crucial to students’ chances of comprehending texts across all subjects.

Different Worlds: ‘Voice’ in Drama vs. Literacy

My new experience prompted me to compare how we teach ‘oral language’ in literacy to how we use the voice as an expressive skill in drama.

The drama curriculum introduces the voice as a tool for exploring characters and relationships. Students progress from sustaining a role to using techniques like projection, pace, pause, and pitch to communicate a character’s intentions. By Years 7 and 8, the curriculum focuses on “voice production” to develop vocal qualities like clarity and contrast.

In summary, drama education views vocal skills through the lens of performance. Students learn to use their voice so an audience can hear them. This contrasts sharply with literacy education. The explicit teaching of ‘voice’ in drama is not framed by the phonological awareness required for learning oral language. The writers of the drama and literacy curricula simply hold different views of what constitutes essential knowledge.

A New Synthesis: Reconnecting with Phonetics

Remarkably, teaching students phonemes rekindled my love for teaching “speech and drama” as a young teacher. Before 1985, a prerequisite for teaching senior secondary drama in my home State of Western Australia was completing Grade 6 Speech & Drama. Through this, I learned the art of voice production, speech articulation, and phonetics. It was foundational to the embodied way I taught expressive skills.

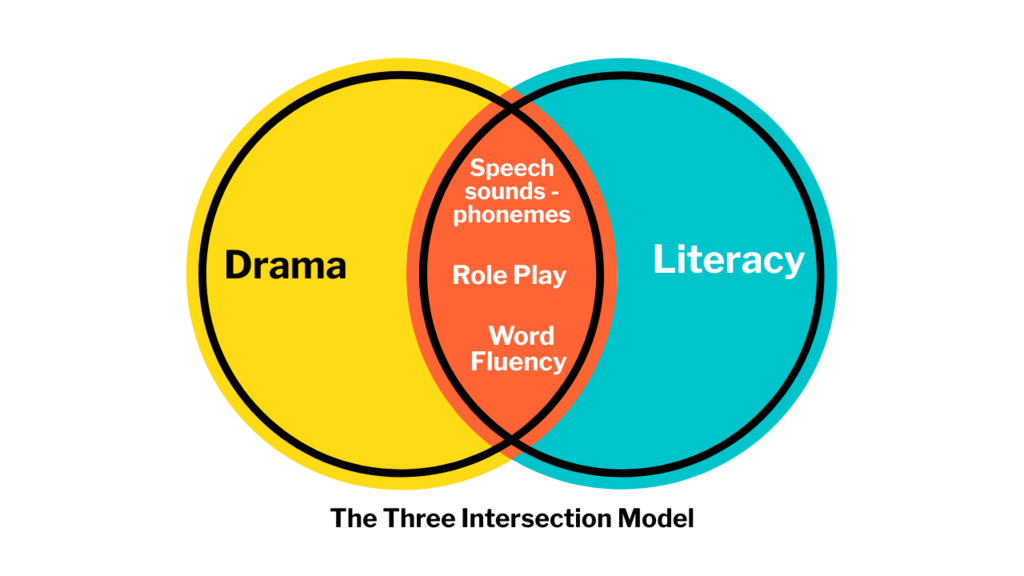

What is clear to me now is that Structured Literacy requires me to motivate students to do detailed, difficult, and repetitive tasks. The “science of learning” shows this is necessary to achieve automaticity. Consequently, I am reviewing my previous attempts to blend “rigour” and “fun.” I now plan to limit myself to focus on three key intersections between drama and literacy: phonological awareness, role play, and word fluency.

- Phonological Awareness: Literacy requires the ability to hear and manipulate sounds (phonemes) to decode words. Drama requires clear articulation of those same sounds to be understood. This is the most direct technical link. When a student reads a line of text, they can practice both decoding and using tone to indicate inferential meaning.

- Word Fluency: In both drama and reading aloud, fluency is about more than speed. It involves accuracy, expression, and comprehension. Role-playing and performing scripts give students an authentic reason to reread texts. Their goal is not just to “read better,” but to “perform better”—a far more motivating goal.

- Role Play: This is where the cognitive turn becomes so powerful.

The Cognitive Science Behind Role Play

Since 2002, cognitive science has offered critical insights into how our minds engage in role play. Theatre historian Bruce McConachie, in his work Evolution, Cognition, and Performance (2015), examines these intersections. He uses the “enaction” paradigm, which asserts that cognition is enacted through the interactions of our minds, bodies, and environment.

McConachie suggests the human brain evolved and specialised for role play. It wasn’t just a learned skill but a fundamental cognitive adaptation for navigating our social world. This power to improve inferential reasoning is exactly what reports on “process drama” methods have shown in John Nicholas Saunders’ 2021 & 2024 reviews of School Drama™.

According to McConachie, neuroscience provides further clues. Learning corresponds to forming and reinforcing neural pathways. When we use emotions in learning, a common feature of role play, we improve memory retention and recall. Effective role play engages both our “cool cognitive system” (hippocampus) and “hot emotional system” (amygdala), leading to more robust learning.

A Practical Plan: The Dr. Seuss Reader’s Theatre Festival

My first goal is to help older students who feel shame about learning decoding skills. I am creating units of work infused with dramatic play that allow them to practice phonological awareness, word fluency, and role play. After discussing this with literacy leaders, I believe the mainstream English classroom is the right context, rather than a small intervention group.

I will begin by writing a term unit for my Year 7 classes. The unit, titled Dr. Seuss’s Reader’s Theatre Festival, will give students an authentic purpose for their work. They will read Dr. Seuss texts as a reader’s theatre performance for an invited Foundation-to-Year-2 audience. This provides a clear production timeline that necessitates practice, re-reading, and rehearsal.

As a theatre historian, I am excited to support the status of decoding by associating it with the tongue-twisting, comic, and zany “nonsense” of Dr. Seuss. It is a “less is more” approach that I believe can make a real difference for students who have fallen between the cracks.