“Learning and teaching should not stand on opposite banks and just watch the river flow by; instead, they should embark together on a journey down the water. Through an active, reciprocal exchange, teaching can strengthen learning and how to learn.”

Malaguzzi, L. 1998, ‘History, ideas and philosophy’, in Edwards, C. Gandini, L. and Forman, G. 1998, The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Approach, Ablex Publishing, Greenwich (p83).

Like many teachers, I’ve dealt with many theories, policies and manifestos on optimising the relationship between teaching and learning.

These include those produced by State and National education departments who draw up curriculum policies, such as Victoria has done through its Victorian Teaching and Learning Model 2.0 (VTLM 2.0) and High Impact Teaching Strategies. These bring together “10 instructional practices that reliably increase student learning when they’re applied.”

Furthermore, for the last decade at least, and with a new urgency since the coming of AI, we need to consider the impact of cognitive science research on curriculum development. For instance, I completed the Coursera MOOC Learning How To Learn, one of the most popular courses on the learning platform. Its facilitators Professors Barbara Oakley and Terrence Sejnowski now lead the research on managing the risks of artificial intelligence on learning.

Cognitive science has also impacted on my understanding of creativity and philosophy through Harvard’s Project Zero; cognitive linguists and philosophers (e.g. George Lakoff, Mark Turner); embodied cognition by theatre and dance historians (e.g. Bruce McConachie, Nicola Shaughnessy) and through sociologist Erving Goffman’s work on organisational management.

Dealing with the burden of a great potential

Curriculum content creation is nothing if not obsessed with bridging the gap between teaching and learning! And what does that mean if it isn’t about making something change for the better in the learner. However, we possibly forget that teaching too could be seen as a form of learning.

I was introduced to the idea of teaching as learning in my first school appointment, when I was barely 21. The following Peanuts cartoon took pride of place in the principal’s office. I’ve used it over the years to focus on the fact that a student’s learning is inseparable from what a whole lot of adults believe and say about what he/she can/not do. But what message do they give young people about how best to learn?

We must also realise how it’s not formal curriculum policies that deliver the best of teaching or learning. At best, they are the outline that shapes our practice. The colour and vibrancy comes from our grit, rigour, resilience, perseverance, experimentation, inquiry and mastery, and these are just some of the terms associated with the best of human learning.

What learning is recognised and rewarded?

In 2020/2021, I participated in Learning Creates Australia‘s National Social Lab looking at “solutions around new metrics and a better recognition system for a range of pathways beyond school”. The project vitally highlighted problems in our current system. It brought together a significant group of people, nationally and globally, who are collectively saying that the ATAR system needed to change.

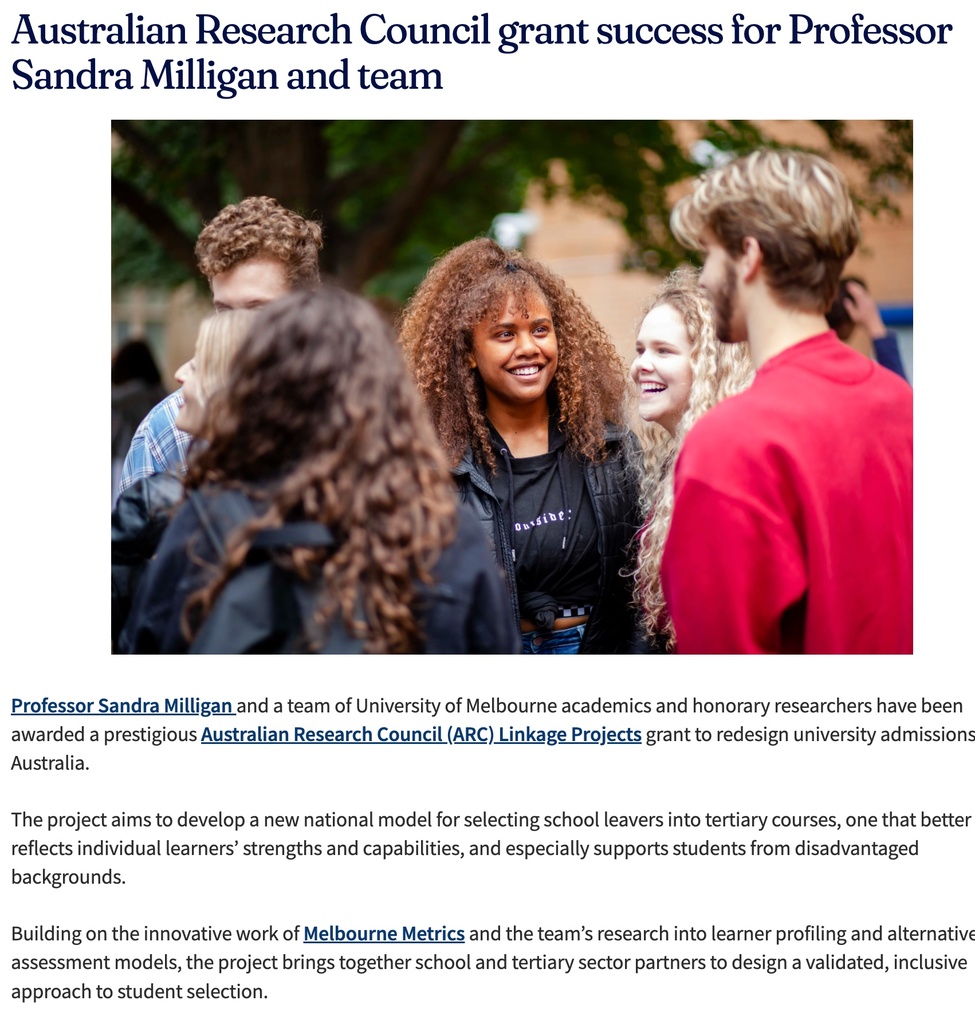

Professor Sandra Milligan and her team at the University of Melbourne, published Recognition of learning success for all, a report which brought together the work of schools, communities and Learning Creates Social Lab teams. Professor Milligan summarised the existing case for change in the following terms:

Key indicators and metrics are not improving, or are improving only slowly. Many young people are still not completing school. Standards of attainment in some core areas of learning are falling. Even for those who complete school, transition into a satisfying post-school pathways is often difficult and slow and not conducive to confidence.

Five years later, in July 2025, Professor Milligan has won the chance to change ‘the system’ so that “any school leaver who applies for entry into a Uni or TAFE will not be represented just by a number or a rank They will be able to match their particular strengths to where they will succeed best. And tertiary education selectors will have the information they need to better understand the young person and make sure they can succeed.” (https://education.unimelb.edu.au/news-and-events/research/australian-research-council-grant-success-for-professor-sandra-milligan-and-team)

What happens when teaching and learning seek different goals?

An anecdote pops into my head from a talk to postgraduates by UWA’s Vice-Chancellor Fay Gale in 1990. I was just setting off on my doctoral adventures. Professor Gale shared the story of how water-collecting receptacles found above limestone caves along the Great Australian Bight were not considered for decades by researchers as human-made creations.

Why? The European researchers refused to view the people living in the caves as capable of technology that could funnelled water from the surface to their dwelling places below. Rather, they were prepared to investigate how wind and water had produced them! Of course, the story plays into debates around the ‘pygmalion effect’ and other theories of ‘self-fulfilling’ prophesies. However, for Professor Gale, it best illustrated how cultural annihilation is most effectively realised by narrowing human learning, in ourselves as well as others.

The message for me as a teacher is that my learning must be viewed in relation to how I form questions about the knowledge I seek to identify, analyse and confirm. The ethos of learning how to learn moves ahead of capturing a result.

Curriculum for a common humanity

It is clear to me that teaching and learning are powerfully challenged today by technologies that make content cheap and fast. That means resources, learning events and timely connections can fly like never before. However, what remains challenging are the ethical and political values that shape their use in our mission to bring together teaching and learning experiences. In turn, this impacts how school communities, States and Nations communicate value of viewing life from the perspective of being education people.