My involvement in the implementation of assessing and reporting against standards began in the mid-1990s. Nearly thirty years later, however, I seriously doubt whether we’ve made sufficient inroads into parents understanding school assessments based on learning progressions. 1

Parenting & Educational Progress Maps

Blaming millennial-aged or younger parents would not be fair. For instance, recent research from the Australian Institute Of Family Studies shows how that age group highly favour courses that focus on child development. They say it allows them to view their role through a much more productive lens, minimising more negative ways of managing children’s behaviours.

To explain what children’s development looks like, how it works and what threatens it, communicators need to use meaningful language. Metaphor is a time-tested device that can be used to enhance the understanding of parenting concepts. … The successful candidate was a ‘navigating waters’ metaphor. This describes parenting as a journey that requires skill and support, where one may encounter smooth or rough seas and where safe harbours and lighthouses can protect parents from these challenges.

This should give teachers and school leaders hope in educating parents to better understand education standards and progress maps. But in the time-starved busyness of all schools and their crowded curriculum, educating parents on learning progressions is just another complex thing to do (or avoid) in an ocean of complex content demands.

My current work on ‘thinking skills’

My question is, how do we tell parents the positive story of the efficacious practice of using developmental frameworks? And how do we do so without adding to the load that home-school relations already carry? I have been working to solve such a challenge in my own work with respect to learning progressions in critical and creative thinking.2 However, the truth is that complexity grows like gremlins. For instance, critical thinking in the education jurisdiction in which I live, in Melbourne Australia, now includes dealing with three maps?

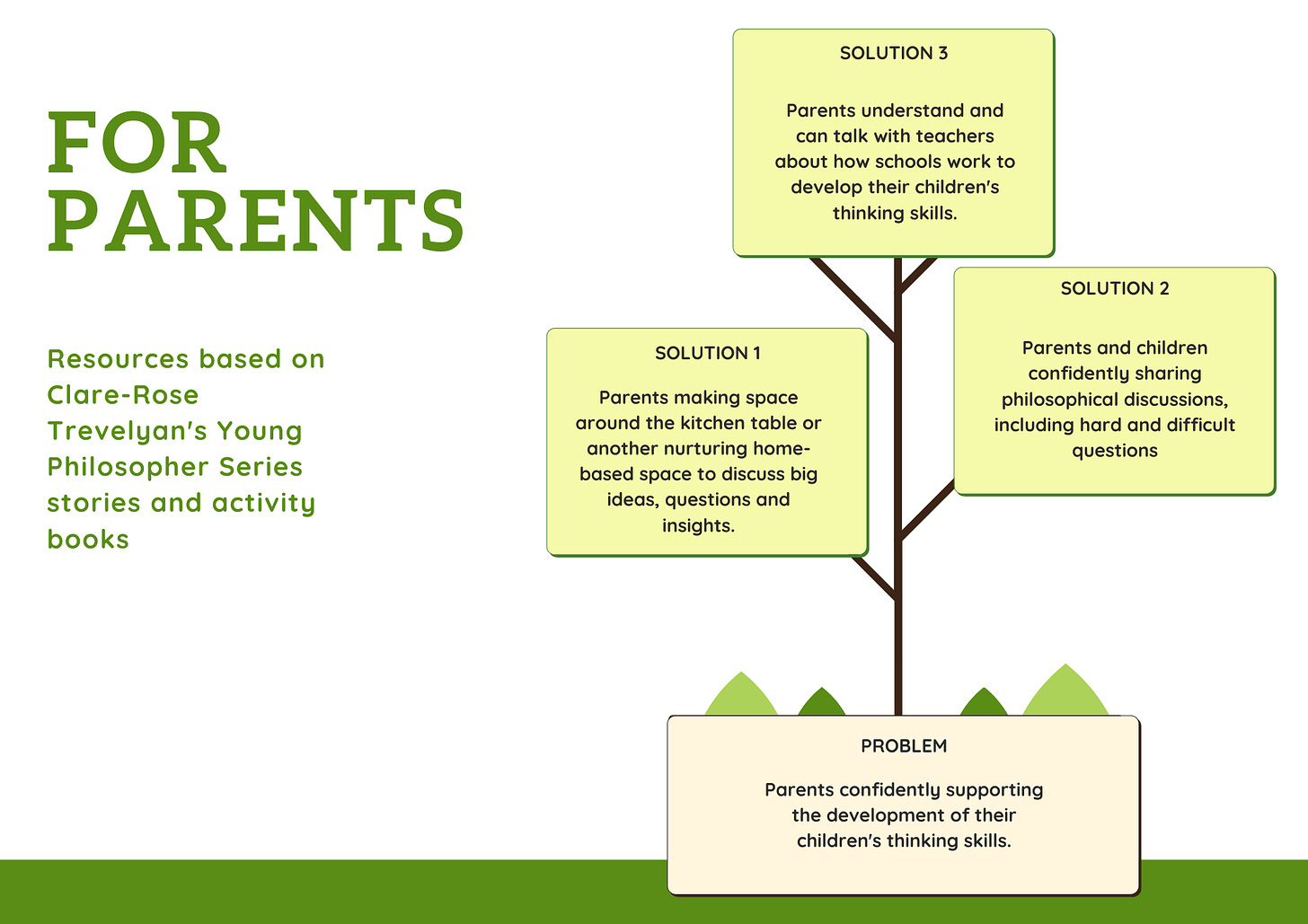

For this reason, I’m turning my attention more and more to the narratives we might use to keep school communities thinking and talking about thinking skills in order that children, parents and teachers develop a shared sense of progress. My approach has led me to devise educational resources with children’s author Clare-Rose Trevelyan around her Young Philosophy Series of four interactive activity books (shown below).

I do so in the confidence that it is Clare’s passion that her stories about lost characters (in The Book With No Story), absurd but determined explorers (in Why Are We Here), regretful aliens who cause environmental destruction (in One Thing And And Anothers) and wordsmithing (in The Fake Dictionary) support the development of children’s critical and creative thinking. So rather than focus on the formal end of learning, Clare and I are in the process of creating resources that support parents in having philosophical conversations with their kids. Next, we ask, how could such beautifully productive thinking together out loud, also build parents’ confidence to discuss with teachers children’s use of thinking skills.

Yes, it’s a kiss-it-better-with-a-band-aid-strip approach!

The band-aid commercial which gave rise to kiss it better with a band-aid strip shows my age. But as I consider the complexity of learning progressions and thinking skills, I’m reminded it’s the power we wield that shapes our ability to solve problems. Parents are overwhelmingly the dispensers of band-aid solutions. For that matter, so are classroom teachers, except that their professional status put them on the inside of the system.

But let’s look at it another way. A temporary band-aid solution can be a very important first response to a physical injury. Furthermore, there are many types of band-aids, as the band-aid business is a well-developed one. In any case, this is how I see myself making a positive difference to the complex home-school relationship at the heart of why parents need an understanding of learning progressions.

Honouring what happens at home.

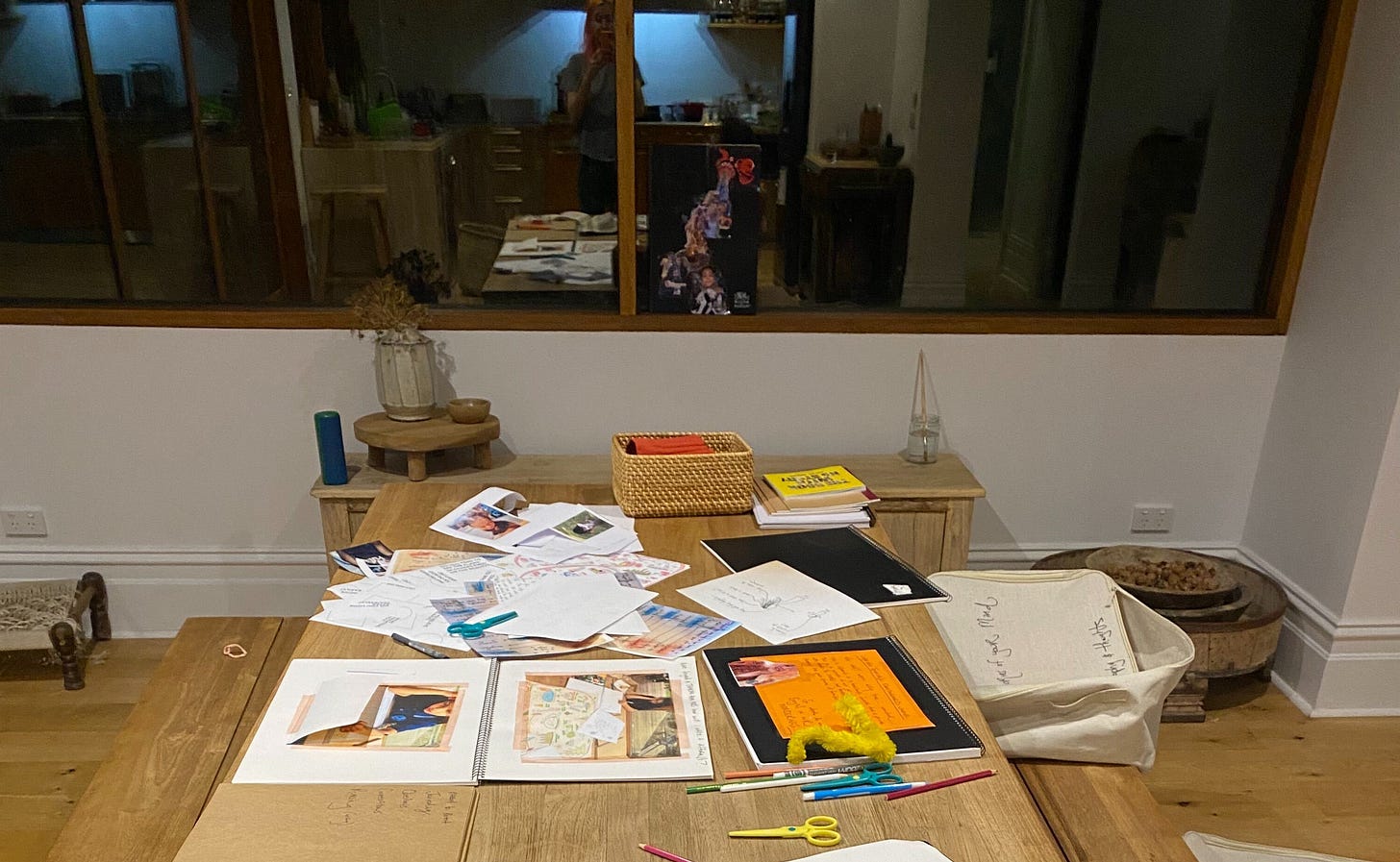

In the four years I’ve worked with Clare, I have come to deeply admire how she has reclaimed the imaginative processes of her own childhood. Finding an unexpected book on her mother’s bookshelf in which she discovered the word apeirophobia.3 Keeping journals from the age of four in which she draws and creates characters made of many things, like string and ribbons. Wanting books in which she can draw and write all over. Finding her grandmother’s mementoes scattered around the house – her diaries, thimbles and sewing things, her hatpins. Remembering family discussions around the kitchen table.

I believe that Clare develops each of the four books in the Young Philosophers Series as part of her evolving manifesto. One, which helps her explain to her own children how thinking and doing are related.

Thinkers and doers

Remarkably, by doing so she hits against one of the oldest prejudices in education. Namely, that some of us are ‘thinkers’ and others are ‘doers’. The separation has called up both snobbish intellectualism and ignorant anti-intellectualism. Thankfully, researchers of Embodied Cognition and the Conceptual Metaphor Theory have shown the absurdity of the duality. For example, in his comprehensive account of the research in Scientific American, Samuel McNerney says this,

It means that our cognition isn’t confined to our cortices. That is, our cognition is influenced, perhaps determined by, our experiences in the physical world. This is why we say that something is “over our heads” to express the idea that we do not understand; we are drawing upon the physical inability to not see something over our heads and the mental feeling of uncertainty.

By contrast, viewed from Clare’s sense of creativity, both thinking and doing matter as she grows her vision for deeply connecting children to participate in conversations with their first teachers, their parents. In fact, I believe she demonstrates how writers and artists (a term she resists) use the basic processes which we all use in our human communications and interactions towards new insights.

It follows then, that as a curriculum designer I can do something with her about strategically placing band-aids on the complex body of human learning. Yes, there are thousands of small cuts that have damaged our creative potential as parents. On the other hand, the heroism of dealing with flesh wounds (shown wonderfully by Monty Python) has to be better than cynically festering and saying the job is too big to fix.

Picking up on trends

We all have a strategic role to play. It’s THE crucial matter we deal with in 21st Century Skills, Enterprise Skills and as part of the suite of skills for being an entrepreneur. All revolve around critical and creative thinking.

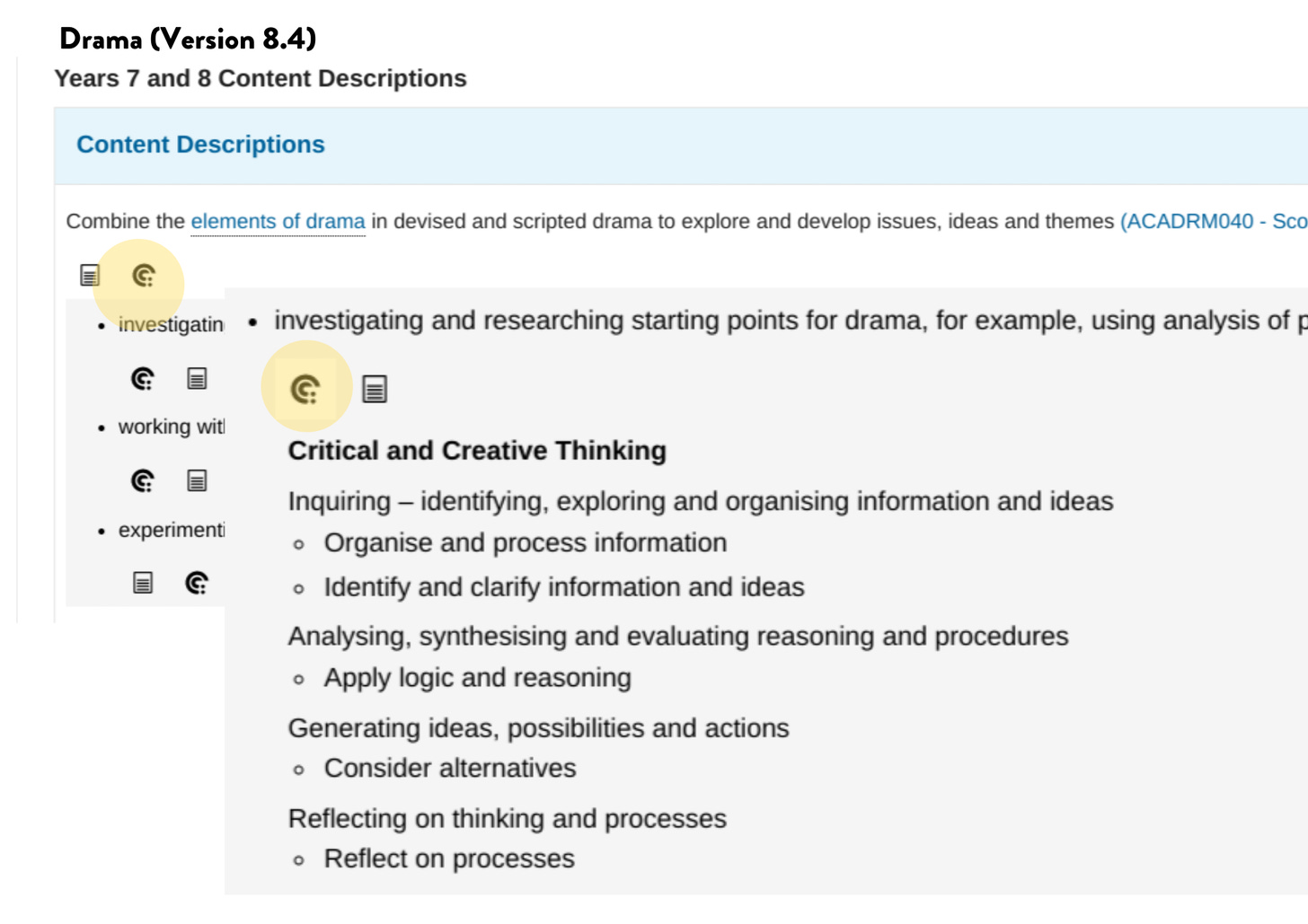

So, let’s deal with the details by which labels like thinking skills get hazy. This is where we need systems and institutions to tell us what’s what. In Australia, that means looking to the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) and our State-run education department (e.g. for me in Melbourne it’s the Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority).

Speaking from experience, the documents do a pretty good job for professional educators. But, do the same documents inform parents about helping their children be more employable? No. Do they allow them to advise children, as the philosophers hoped for everyone, on how to have a good life? No! Is there anything in parents’ own primary or secondary schooling that would help them understand that thinking skills is not a subject but a capability? No!

Bring on expert knowledge, right?

Consequently, over the last four years, I’ve briefed Clare on many aspects of the educational trends that impact teaching and learning thinking skills. For instance, on

- The Philosophy For Children’s movement. How it has make a positive contribution to shifting how educators view children as potentially great thinkers… as young philosophers in fact.

- Cognitive scientific research. How it has brought to light theories such as the Conceptual Metaphor Theory, Computational Thinking and AI, and a whole band of strategies suitably labelled as ‘brain-friendly’.

Thanks, but no thanks

My pedagogical briefings have usually received a thanks-but-no-thanks response. Consequently, I came to understand that the problem for Clare was far from academic. She wanted to do something important for her children. 4

How were we to arrive at curricula that helped her build a space in which her family might continually meet and listen to each other’s thinking? How could critical and creative thinking skills be part of a space in which thinking was embodied, personalised and connected to school and home contexts?

The Young Philosophers Series & its thinking skills solution.

Ironically, the approach of replacing institutionally-based academic solutions with a personal creative one is a hallmark of working in a startup business. In the case of Everything World resources, Clare’s creative talent and personal circumstances drive our solutions. Not only does her passion bear the responsibility of finding the bulk of the funding for the work, but it drives its collaborative co-creation of products and publications. For instance, Clare worked with illustrator Yongho Moon and eight other visual artists on the second book of the Young Philosophers Series Why In The World Are You Here, with each artist interpreting the nine islands in the story through different media.

Announcing Everything World

In fact, I believe, it was this mix of startup education-that’s-not-school-education that drove Clare to invent Everything World, like a theme park for the mind. Through doing so, she came to announce something remarkable for a writer, that books and stories are not enough. Context is more important. And so she sought out a space in which she and her children could play, listen to stories, draw over books and harness the power of philosophical discussions. She proposed to them… what if the mind was an exciting theme park, each ride and attraction embodying what it means to do the thinking.

Most importantly for me, this allowed me to use the learning progressions on critical and creative thinking while simultaneously freeing parents to model their curiosity and passion for what their children think, feel and show.

From Classroom To Somewhere Else

Meanwhile, I knew how to encourage children to tell stories of making progress using the critical and creative thinking learning progression. The starting point can occur at any point in the formal school curriculum.

For instance, I imagine myself back at the beginning of my career, introducing a drama program in a new school that is moving to blend two single-sex schools into one large co-educational one. As a teacher, I have been made aware that drama is the ‘soft’ way that the school leaders want to enable the coming together of two school cultures into one. I create a Lunchtime Theatre Festival to view what drama experiences and knowledge of the elements of drama already exist in my students. I discuss with them the criteria set out in the Critical and Creative Thinking elaborations for their choice of skit or short play they will present at the Festival.

The conversations that teachers have with students resonate with how parents and children discuss philosophical questions. In the common space of relating to children, the experience of critical and creative thinking is common to both parent and teacher. Two things are in operation simultaneously. The teacher is professionally required to measure child development in formal terms, while the parent can instil the love of thinking as a social act between interested people. This is the relationship we support going forward.

Everything World & a ticket to co-create the park

How will this happen through our resources?

Firstly, the idea of Everything World itself is revealed in a map drawn in outline in black and white. As such, it represents an unfinished creation of a state of thinking, dedicated to the potential co-creative thoughts of children and parents. Yes, there are articulated shapes of signally how thoughts are related to beliefs, values, questions, needs and so much more. However, what makes a theme park of the mind grow requires many minds, working together to show how idea by idea is realised in individual lives, with family and friends.

From mapping ideas to whole ways of being

While the vision of the whole plan is important, valuing the process by which the detail of ideas is realised must be shown to be of even greater importance. That is where the challenge and growth are situated. Consequently, we focus the first of our resources on just five attractions in front of the park. In dealing with each attraction, parents and children get to nourish their time together with many beautifully challenges.

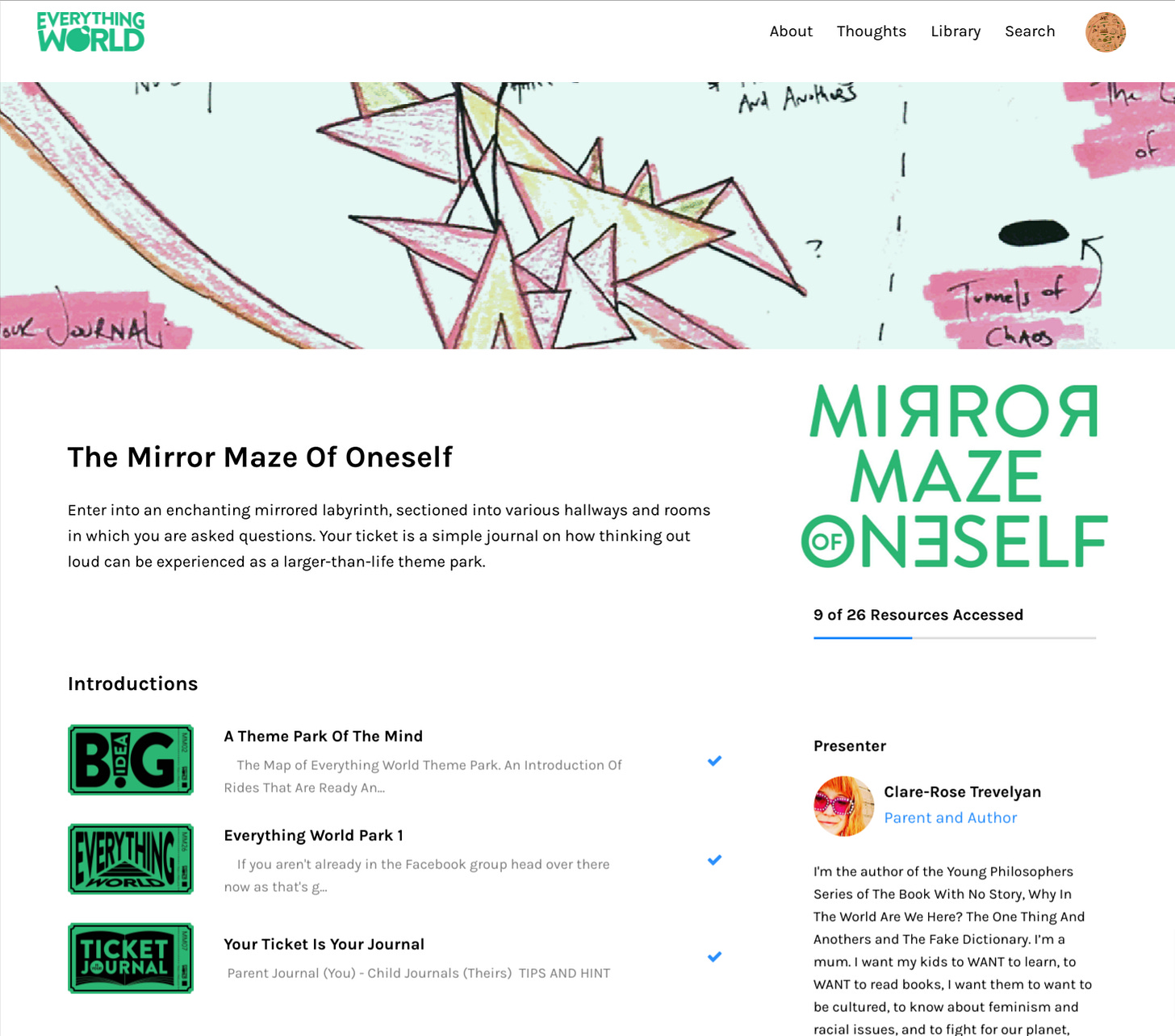

The Mirror Maze Of Oneself

Entrance to the park begins in The Mirror Maze Of Oneself, which is the catalyst of thinking out loud together. The ticket to enter is taking up a journal that records both the parents and children’s developing understanding of thoughtful interactions. Indeed, the journal is one of the oldest forms we have of thinking-about-thinking, that uniquely human practice of growing our own conscious thoughts.

The purpose of the Mirror Maze is to get everyone used to asking questions – good questions, silly questions, hard questions and knowing what exactly are philosophical questions.

The Bumper Cars Of Everyone

The attraction of THE BUMPER CARS OF EVERYONE is based upon a book Clare wrote called THE BOOK WITH NO STORY. The book is an assemblage of characters who have run away from the author’s own journals. They are unhappy and bored by the stories she intended to place them. The characters are morphed in the attraction into creature-rides, held together by the cryptic descriptions of their profiles.

What’s fabulous is that there are 52 of them – one for each week of the year. Ideas clash and conflicts spark debates, all needing to be resolved in coming to know and grow empathy for them. In essence, Clare models for parents and children how creating inside and outside stories moves cryptic clues about one another into whole narratives.

The Lake Of Meaning

Once you start thinking in the theme park about WHO YOU ARE, WHO YOU ARE NOT, and WHAT DO I KNOW ABOUT EVERYONE ELSE, you can begin to really investigate WHERE you are. As you read the ATLAS of Why In The World Are We Here? natural questions occur about what allows you to belong somewhere. Feel free to write and draw all over the words and artwork as you explore this text as a family.

The Wonder Wheel Of Contradiction

Surely you may have noticed by now, that most people you know and love, are, well, both one thing and the exact opposite at once. They go in opposite directions at once and then wonder why they have so many problems. With that idea in mind, the Wonder Wheel Of Contradiction is a much-tested and tried quest for figuring out the reasons for ‘why it is so’ and how it couldn’t possibly be. What happens on the ride is based on two aliens, Rio and Huxley from The Planet of Stuff. Clare tells their story in The One Thing And Anothers.

The Ghost Train Of Change

The ghost train always tells a historical story written by a child. It operates like a traditional cart, rolling through a haunted house, but the “ghosts” and the whole daring experience is created through hologram-like visuals so that they can be changed by whoever is in charge of telling the story that day. This ride is based on THE FAKE DICTIONARY. The point of the book is that someone, somewhere, somehow made up a particular word to be meaningful and useful.

Accessing the attractions

These experiences are accessible online in bite-sized resources that can be revisited time and again. For instance, this is the introduction to the collection of twenty-plus resources for the Mirror Maze.

Clare At The Kitchen Table Guides

Clare is adamant that busy parents remain in the position of taking what they want when they need the resources. So, the guides for activities around the attractions all begin showing the activities she has devised for her own children.

So this is our north star – Clare’s own love of being around the kitchen table with her three children.

In time, Clare would love that we find the billionaire who funds the creation of the theme park as a physical reality. Meanwhile, we’re confident that its imaginative qualities are strong enough for the job at hand, of nurturing philosophical discussions in families.

What drives us is creating an emotionally satisfying space, with engaging activities that parents and children can use over and over again. We know that exploring complex ideas CAN be served up in bite-sized chunks, spiced with enough surprises to help families keep children engaged in big and powerful ideas.

I firmly love the workings of the learning progressions that shape such skills. However, it’s my job now to enable parents to access their understanding of them, not as professional teachers do, but as part of the pleasure of being people showing children how they are continually learning to be critical and creative thinkers themselves.

——————————————————————————————-

- A learning progression is a continuum that maps key stages in the development of a learning domain (e.g. literacy and numeracy) from simple beginnings through to complex interpretations and applications.

- I worked in the Assessment and Reporting Branch of the Education Department of Western Australia introduced thinking skills in 1995.3

- Apeirophobia is the excessive fear of infinity and the uncountable, causing discomfort and sometimes panic attacks from thoughts of the infinity. It normally starts in adolescence, but in some rare cases, it can start before then.4

- Interestingly, thanks but no thanks is also the response teachers display when great slabs of curriculum knowledge are piled on them in the hope of improving their teaching.