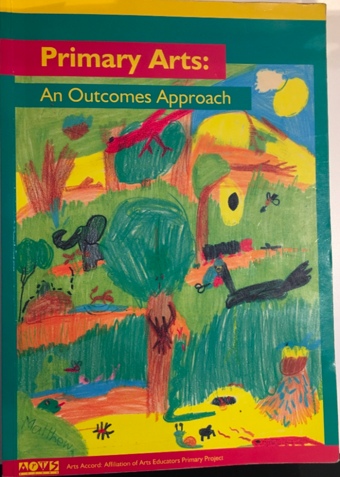

The 1998 primary arts publication

The 1998 primary arts publication I worked on, which brought together a number of cross-curricular arts project for primary schools, is pictured on the right. As the resource was commissioned by five arts education associations, it was my role as chair of the joint committee to oversee the collection of exemplars of arts projects in dance, drama, media, music and the visual arts which showed how they might help teachers assess different aspects of their literacy programmes.

In my preface to the book I described a term-long (12 week) drama and literacy project, which I ran for two hours a week with twenty-five Year One (five/ six-year-olds) students, on the topic of Queensland’s Daintree Rainforest. The drawing used for the cover was by one of the students, Matthew. It serves as a wonderful reminder for me that the reason for choosing the topic came from news headlines at the time which dramatically showed protesters and developers fighting over clearing land which was the natural habitat of the rainforest bird, the Cassowary . Note the black feathered Cassowary in the drawing standing behind the long grass.

While the purpose of the project was ostensibly to create an ‘assembly idea’, both the teacher and I understood that it was my job to realise the ‘world of the play’ in the ‘real classroom’. Or, as John O’Toole explains in The Process of Drama (1992), we aimed to create a form of metaxis of fiction and reality in which the students were placed in a position of negotiating two locations at the same time.

Summarising the learning

In retrospect, I now acknowledge that the collaboration with other teaching artists on the publication meant I was very conscious throughout the project of the quality of the partnerships which ought to exist between the teacher and me as a visiting artists. I further realised that my partnership with the teacher should have been more supportive of her need to assess the children’s learning. So with all the wisdom of hindsight, I believe the ‘rain forest project’ would have been more effective if I had identified key phases where my artistic evaluation of the project coincided with the teacher’s evaluation of learning outcomes: for instance,

- The first phase could have occurred from our mutual acceptance of an overall learning objective for the project , which existed informally in our discussions as ‘exploring sounds, words and sentences in speech in order to express ideas & feelings in the children’s writing of a daily diary.

- The second phase could have focused on finding a way of measuring the children’s ability to speak a few sentences aloud at the start of the project. Again, this was informally in place as I recorded the children speaking as rain forest animals in the first two weeks of the project though mirror exercises and movement/ sound games around the different kinds of animal species in the rainforest: birds, frogs, ants, spiders, snakes etc. The tapes became the basis of the ‘script’ for the children as they created their presentation of the animals both in chorus and through short monologues which all began with sentence structure of “I am a _____ of the forest. I can ____, ____ and _____ .

- The third phase could have been about signposting key ‘extension’ work during the project to mark the depth and breadth of arts experiences I did with the children. I had created charts and other resources based on the drama elements of voice and movement for activities around exploring a) vowel and consonant sounds as onomatopoeia; b) rhyming and rhythm patterns to assist memorisation of lines and c) metaphorical & figurative language accompanied by music soundtracks which let the children hear and move to a group of related terms.

- The final phase which I would use did happen, but only after I had left the school. The children wrote me letters reflecting on their role in the Rainforest Play. The reflection was accompanied with a drawing of the character they created for the play – hence the drawing for the cover of the book. Note that Matthew was a spider in the forest who could camouflage himself against the bark of the tree. And yes, he wrote how he had camouflaged himself to save himself from the hungry rainforest lorikeets.

The rainforest project was a most satisfying for me. However, while the school was very pleased with the children’s work (so pleased that they offered the piece to the Education Department’s “Education Week” programme, staged at a large Westfield shopping centre), I felt that I could have done far, far more in the publication and through other means of publicity within the school community, ‘joining the dots’ to map how the project had assisted, for instance, in the development of the children’s vocabulary: mostly, I could have given the children a voice to speak about the learning they experienced about the rainforest via the arts.