In order to understand the value of dramatic play look at debates around what constitutes essential knowledge and skills at every level of schooling – from early years to higher education.

Most importantly, we need to understand how knowledge, skills and processes are related to, and constructed, by elements of the performing and visual arts. These elements are the building blocks of making meaning: they transform ‘sensory input’ into language through gestures & movement, visuals, sounds and texts to express our experiences, feelings, values and beliefs.

Beginning with the 3Rs

Kay Wood’s Education: The Basics (2011) considers the contexts of education as ‘schooling’, ‘acquisition of knowledge and skills’, ‘the process of learning’ and education’s ‘moral dimension’. Wood’s target audience is the student teacher at university, preparing to enter the profession. She points out to them that unlike other subjects that may require work and effort to understand

…people tend to think they know what education is. It is a familiar topic: a word in daily use. It’s all around us… Politicians of all persuasions continually tell us how important education is for the economy. We are bombarded with messages from the media… Schools are failing, budgets have been slashed, children are not learning… On the bus, in the pub and at the hairdresser’s people are expressing opinions. We may not know much about nuclear physics, but we are all experts on education.

A similar certainty exists around what constitutes essential knowledge in the curriculum.

Most people, remembering their own schooldays would say that schools are teaching essential knowledge which represents a clear and objective way of looking at the world. Knowledge is divided into subjects … subjects are said to represent the best selection of knowledge available. It is knowledge worth having, and is selected by experts for the benefit of students, even if the benefit is not obvious to students themselves. Some subjects are thought to be essential, even if there is disagreement about the relative importance of others. For example everyone needs to read, write and add up, therefore English and maths must be central to the primary school curriculum.

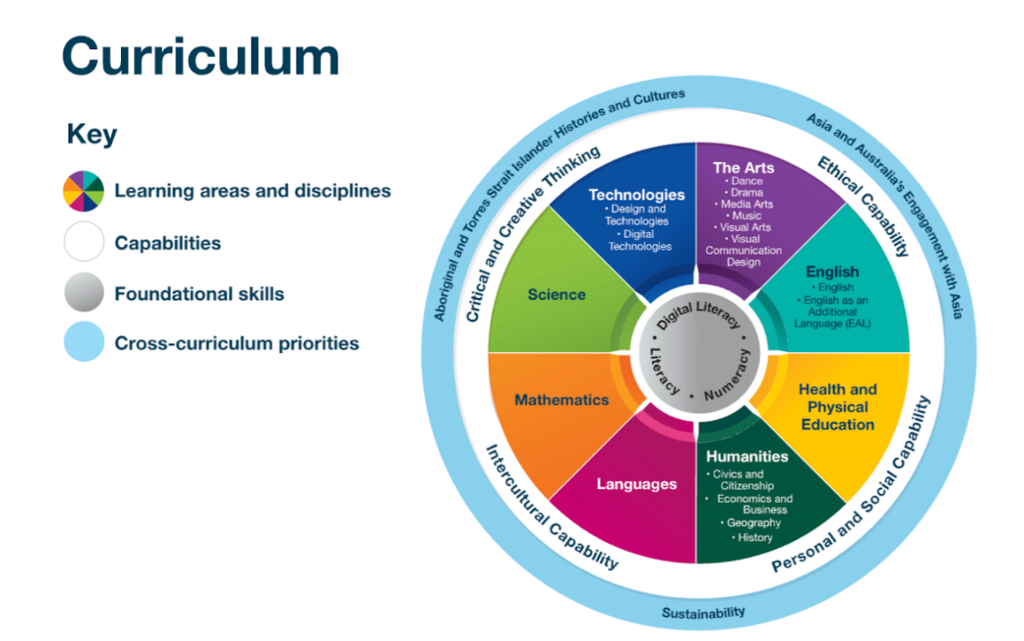

Not remarkably, then, the Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority VTLM2.0 is envisioned with Literacy and Numeracy as Foundation skills, though in 2025 these are augment with Digital Literacy. The rationale describe them as “fundamental to learning across the curriculum” as they are utilised to enable “learning for all students during their years at school”.

Sticking to the basics

From my experience, while this seems an obvious implication of ‘the basics’, cognitive science gives us a more microscopic lens inside the learning processes involved in achieving foundational skills. For instance, let’s consider the importance of oral language to literacy and its importance to the development of reading and writing skills. However, as the ACER’s 2024 report “Unpacking the science of reading research” shows, this is a complex matter. Yes, it is noteworthy to know that oral language is “linked to semantic understanding, vocabulary, morphology and phonemic awareness”, but classroom teachers are required to do more than learn new knowledge, they must apply it, for instance, to their curriculum planning for explicitly and motivationally enabling their students achieve speaking & listening, reading and writing skills. Take the development of phonological awareness show in the report (p.12)

As teachers view the content nominated on the continuum, they would be cognisant of the amount of practice a child would need to meaningful acquire the phonetic awareness of each segment. This is not because the ‘end game’ is not ‘segments’ but the meaning synthesis of whole, in short, the deep awareness of the importance of being a successful communicator.

The need for frequent exposure and practice of skills that is explained in the “The Memory Paradox:

Why Our Brains Need Knowledge in an Age of AI” (May, 2025) through neuroscience and learning behaviours needed not to cognitively ‘offload’ learning tasks to devices, especially AI enhanced. Focusing on the deeply intertwined ways in which declarative and procedural memory systems, the main message presented by the five authors (Barbara Oakley, Michael Johnston, Ken-Zen Chen, Eulho Jung, Terrence Sejnowski) is the importance of the Memory Consolidation Processes that requires the use of the brains two memory systems: namely, how the two systems show that “deep learning is a matter of training the brain as much as informing the brain.” (p. 15) Perhaps more interesting still, are their observations on how “Reinforcement Principles” used in training AI thinking has come to illuminate human memory formation.

This convergence between human memory and artificial learning systems reveals a profound insight: prediction errors drive learning across both domains. This parallel explains why knowledge internalized in memory enables far more efficient learning than constant cognitive offloading to external devices. When we consistently outsource thinking to technology, we effectively bypass our brain’s natural reinforcement learning mechanisms—the very pathways that build and strengthen neural manifolds supporting sophisticated thinking. These findings also contradict popular notions of unstructured discovery learning, demonstrating instead that developing expertise requires structured

practice with clear, timely feedback that allows our reinforcement mechanisms to optimize neural representations. (Sejnowski, 2024)

Questioning how to view the basics!

Consequently, bringing dramatic play into the classroom requires understanding how foundational skills of literacy, numeracy and digital literacy are related to arts elements, and in particularly drama elements. The term ‘element’ refers, in essence, the components that can be treated and assembled to build non-fiction and fiction texts – oral, written and mediated.