I like nonsense. It wakes up the brain cells!

Dr Seuss

Asking questions is the foundation of all good jokes…

Did you hear about the one…? What do you get when you cross a sheep with a kangaroo? Riddles and jokes are parented in the human brain in order to actively grapple with making meaning.

Interestingly, the verb ‘to read’ is etymologically related to the verb of ‘to riddle’.

Furthermore, neuroscience can explain the physiological and psychological importance of laughter for human cognition.

When we laugh, we relax. As anxiety decreases, our capacity to retain information expands. Jokes also prompt what experts call “expectation failures,” memorable instances of cognitive dissonance that, in forcing us to grapple with what’s just been said, aid retention. In other words, the heightened emotion that humour evokes doesn’t just make it easier for us to hit upon insights we otherwise wouldn’t–it also helps us remember them.

The Surprising Link Between Laughter & Learning, Fast Company (2016)

Apparent we rarely laugh when we are alone! So, in the search for understanding human cognition we might also remember what makes up that connection.

Humor shows students that we are human, that we see them as human, and that we are making an emotional investment in the relationship. Not surprisingly, principals who share humor at school have teachers who report higher levels of job satisfaction. Laughter also stimulates right hemisphere to right hemisphere social-emotional connection between people. Thus, humor serves the multiple functions of enhancing social connection, decreasing stress, stimulating brain growth, and enhancing neural network integration The Connection between Learning and Laughter

Exploring uncertainty, laughter and learning

As a teacher, who worked as a theatre director in community theatre, I have experienced the tension between working in a conventional work setting, and viewing artists in far less secure positions, waiting for their next ‘gig’. I know that the world of work throws up the hard-fought struggle for an 8-hour day with all its accompanying benefits, like annual holidays. Conversely, I’m aware that securing the next ‘gig’ also comes with a history in which fair work contracts are difficult to negotiate for seasonal and experimental creative work.

It’s remarkable, in fact, to view how the Creative and Cultural Industries hold hundreds of years of experience of amateur and professional performing and visual artists. From the time of the Industrial Revolution, the growth of a mass entertainment industry it was transformed by entrepreneurial efforts, for instance, of many actor-managers navigating the tensions between risk-taking and opportunity-seeking businesses and fair and safe employment conditions.

Today, the implications of these two contrasting ways of working have been brought into sharp focus by the technological disruption of the workplace which has given rise to the start-up ‘gig economy’, which is now dealing with the unprecedented changes made by artificial intelligence. As the ‘god-father of AI’, Professor Geoffrey Hinton, explained on Bloomberg News on November 3, 2025

We’ve never had things almost as smart as us, which we have now, or things smarter than us, which we’ll have soon. We’ve never been there. We’ve had things in the Industrial Revolution that got more powerful than us, but we were always in charge of them. You know, a steam engine is just a lot more powerful than a horse. But we control the steam engine. This isn’t like that. Also, if you got unemployed because you used to do ditches, now you have to do something else, you could get a job in a call center. But now those jobs are all going to go. It’s not clear where those people go. Some economists say these big changes always create new jobs. It’s not clear to me that this will. And I think the big companies are betting on it, causing massive job replacement by AI, because that’s where the big money is going to be.

How should we be preparing our students?

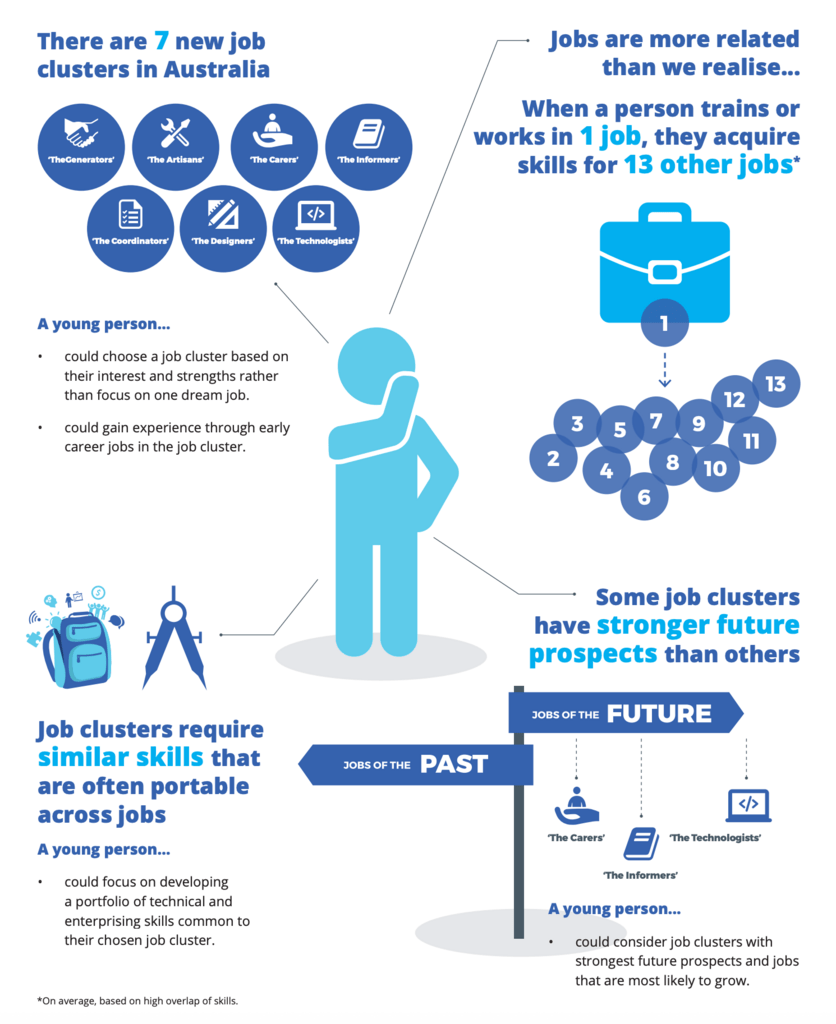

A good place to start is to follow Jan Owen (AO). I acknowledge the message about enterprise skills of her visionary work through the Foundation For Young Australians. However, as I know schools are time-poor places, I wonder about their capacity to implement the Foundation’s compelling case for teaching ‘the new basics’ (2014, 2015 and 2017).

Nonetheless, the FYA has made a remarkable start through their research reports to both identify the skills needed and to contextualise how they should be viewed through a ‘new work mindset’ of transferable career options.This involves focusing on developing skills that are portable across various roles and industries, enabling a more dynamic and adaptable career path. Key transferable skills include communication, problem-solving, creativity, leadership, and adaptability.

As far back as 2018 (an eternity of time in the rapid changing environment we now live), the NSW Government published ‘a conversation starter’, Thinking for the future – preparing students to thrive in an AI world, in which it pointed out how important teaching critical and creative thinking skills should be prioritised in the curriculum. With regards to the thinking skills capabilities in the Australian curriculum framework it stated in agreement with Peter Ellerton, founding director of the University of Queensland Critical Thinking Project:

The design of the Australian Curriculum, in positioning critical and creative thinking as a general capability, also highlights their perceived importance across the eight key learning areas – English, mathematics, science, humanities and social sciences, the arts, technologies, health and physical

education, and languages. This organisation may become increasingly important as, in all subject areas,

students will need to sift through increasing amounts of data, understand the origin and intent of its source, make decisions as to its accuracy, and determine if they need to actively seek out additional information to objectively inform decisions they may make. Viewed in this light, critical thinking becomes

an important ‘cognitive sieve’ for large bodies of information, and an essential skill for people to synthesise, analyse and evaluate information. As Ellerton notes: “No school could teach students all the knowledge they need to survive in a rapidly evolving society. But we could teach them how to think in a way that works for the knowledge they will learn in the future. (p.5)

Perhaps most interestingly, the report pinpoints the specific importance of the teacher’s behaviour in influences a “student’s self beliefs about their own creativity. It explains that

Ronald Beghetto, Professor of Educational Psychology and creativity adviser for the Lego Foundation,

highlights the pivotal role of the teacher stating: “one of the most direct and potentially influential ways that teachers can support the development of student’s creative self-efficacy beliefs is to provide informative feedback on their creative potential and ability.” Research has found this teacher behaviour to be the “strongest unique predictor of middle and secondary student’s self beliefs about their own creativity.” (p.6)

Looking back to understand how I got here.

In 2002 I began to seriously ask myself what was behind Dr Seuss’s belief that nonsense wakes up brain cells. There’s a whole story I could tell about how I set up the Biscuit Factory Arts Centre in South Freo (WA) and became obsessed with putting on NONSENSE PROJECTS blending Philosophy, Drama and Animation. In 2003, I ran the first ‘Drama and Philosophy’ workshops with philosopher Dr Laura D’Olimpio.

Laura later wrote about our approach.

We started the workshops with a series of problem-solving activities and get-to-know-you games centred on the notion of questioning. Questions are crucial to the thoughtful mind; many philosophers would argue that they are even more important than the answers, as Howard Gardner (2004) argues. To ask questions is important as a practical tool that assists us in life: it is the way we process information, discover new information, and expose any problems with arguments or ideas. To introduce this topic to the children, we showed a series of images that were taken from the Wearable Arts Festival, which is held annually in Nelson, New Zealand. The Wearable Arts display their entries in a theatrical, fashion-show production that incorporates music, lighting and choreography. Prizes are given for the best creations. We asked the children to think of any questions, besides ‘What is it?’, that they would ask about the object or to the object. The intention behind this activity is to generate lots of different kinds of questions, not to answer them. We shall see that some of these questions may have answers and some may not, and some may have many answers.

We intentionally attempted to create a community of inquiry (a term used by the Philosophy In Schools movement) through our work. So, instead of getting students to ‘make up a scene’ through a free-flowing improvisational activity, we strategically intervened into their creative process by placing different swatches of coloured cloth on the floor as a way of embodying conscious decision making into their creative process.

The children used our questions as provocations to reveal both the environment and atmosphere of their stories and its characters’ motives and moods. In turn, we observed how the children got better and better at asking each other questions and attributing specific meanings to the narratives.

To laugh or not to laugh? It’s not a silly question!

So, to laugh or not to laugh? It’s the furthest thing from a silly question. It’s a diagnostic one. The laughter Dr. Seuss and the neuroscientists describe is the physiological reward for the very “cognitive sieve” our students need. It’s the sound of a brain waking up to an “expectation failure” in a joke, grappling with the ambiguity of a riddle, and successfully making a new connection.

We are now facing the greatest “expectation failure” in human history: a world with “things smarter than us,” as Hinton warns. The uncertainty is profound. We can’t teach our students the answers, but we can build their capacity to grapple. By intentionally creating “communities of inquiry” that embrace nonsense, ambiguity, and creative problem-solving, we give them a safe laboratory to build their “creative self-efficacy.” Laughter, in this context, isn’t trivial. It’s the sound of a community building the trust, connection, and cognitive resilience needed to face a future that is one giant, unfolding riddle.