In the midst of Melbourne’s 6th lockdown, the Australian Council for Educational Research mounted its annual conference from Monday 16th to Friday 20th August.

ACER Chief Executive Professor Geoff Masters kicked off with his provocative address on the Conference theme of excellent progress for every student. We know a lot now about human learning. Why then do we set up the formal structures and processes of school education contrary to its promotion?

Professor Masters goes further still with even more confronting questions. Why do education systems seemed fixed on sorting students into post-secondary pathways? And why was this at the expense of guaranteeing excellent progress of every student in the K-10 compulsory years of schooling?

Not content just to provoke, Masters’ keynote and all 21 presentations over the five days offered a comprehensive solution. Through the practice of learning progressions, they showed, education systems everywhere had a continuum that maps key stages in the development of a learning domain (e.g. reading and mathematics). Individual teachers to education system managers could map learning of every student from simple beginnings through to complex interpretations and applications.

Not what teachers teach but what systems mandate

This is a point that Professor Masters examines by looking at the inadequacies of the systemic structures and processes rather than the work of the individual teacher. The problem, he says, is in the design of an industrial-era assembly line style curriculum.

All students move along it at the same rate. Each year, the same curriculum is delivered to all students who are given the same amount of time to master it. They then move in lockstep to the next year’s curriculum where the process is repeated. Students who have not mastered the content of the current year’s curriculum and lack the prerequisites for the following year’s curriculum move on regardless. Other students, who may not have required a full year to do this, are unable to advance to a more challenging curriculum until everybody moves in unison. (Masters 2021, 1)

A Pivotal Reform

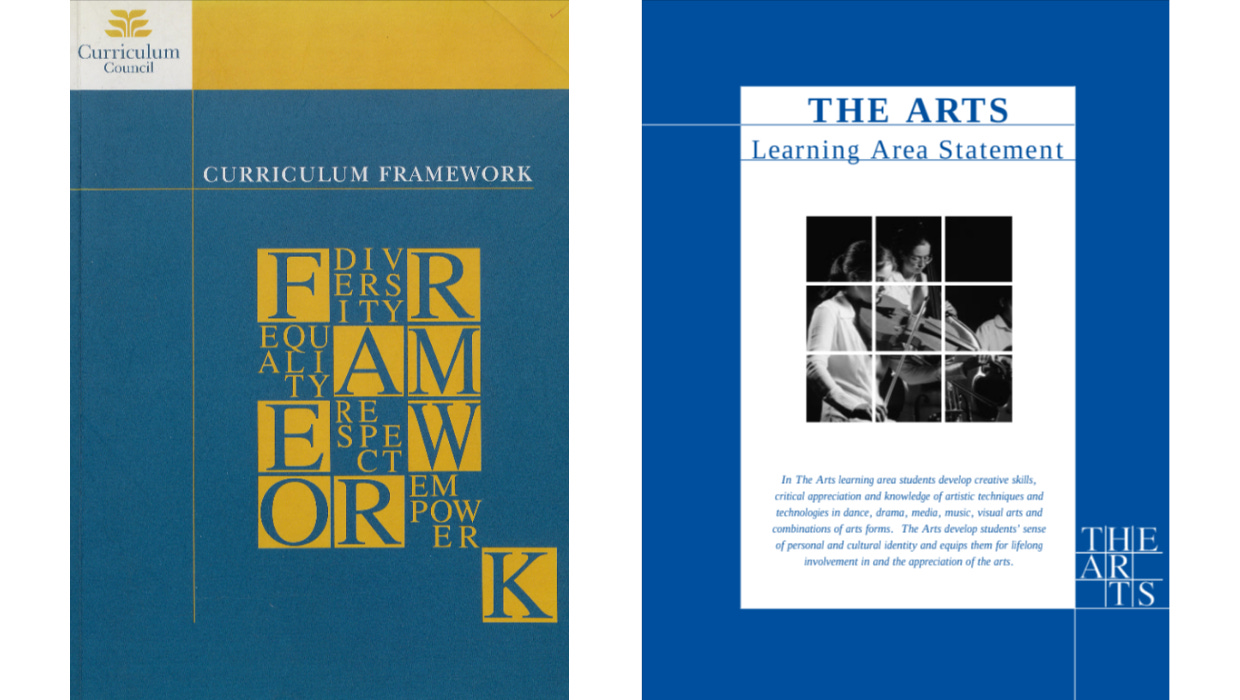

I understood the importance of Professor Masters’ and other conference speakers’ views on learning progression because of my own involved in the move to an outcomes-based education founded on the formal mandated of ‘progress maps’.

In 1996, I was a curriculum writer and researcher in the implementation of the Curriculum Framework of Western Australia (1997). Firstly, I worked in the Assessment and Reporting Branch for the Education Department of WA, working on the formal restructuring to learning outcomes as strands, substrands and pointers. Then later, I was a district-based Curriculum Improvement Officer to refine and implement WA’s Student Outcome Statements. Remarkably, my specialist knowledge of drama education readily transferred to articulating key learning and assessment principles for K-10 students.

Curriculum reform needs more than vision

What I experienced as the Education Department of WA decentralised its curriculum offices and rolled out it approach to devolving the personalisation of curricula to schools was the disconnect between a new curriculum vision and its implementation. In particular, an imaginative implementation of how school-based curriculum creators might realise and validated a once in a century reform.

It seemed to me that, as Richard Pountney noted in his 2017 essay on school-based curriculum development, WA education reformers believed that it was ‘something’ all good teachers can do. What’s more, as good teachers are adaptive ones, they can “knock up a good curriculum on the hoof.” He went on to more fully explain the problem.

It assumes that teachers know the curriculum well enough – to have fluency in it and to be able to exercise judgement in what is appropriate and what works – and have the basics skills to select, sequence and pace. However, these basics are not easily acquired – for example knowing how long to spend on a curriculum topic, and critically, when to move on is an essential pacing skill developed over time. Left to chance these sequencing and pacing skills become predominantly in-the-moment, pedagogical decisions – they are focused on delivery – on what I have to teach the next day. Teachers also feel they have little control over the curriculum, and this contributes to a low sense of job satisfaction, with effects on teacher retention.[3]

This was certainly how I experienced the decentralising of curriculum creation in schools as I participated in refining and implementing the Students Outcome Statements. Consequently, over the years they have consolidated into tasks done by

- individual classroom teachers,

- teaching teams,

- middle management curriculum leaders such as heads of departments and assistant principals,

- lead teachers of literacy and numeracy and specialist practitioners, for instance, in the Arts and in Physical Education.

Now School Content Creation Sits Along Publishing Industry & Edtech Companies

I have experienced how curriculum content creators are part of the education publishing industry, employed by the likes of Pearson, Oxford University Press and a myriad of small independent publishers. This is a place which I have inhabited in writing six textbooks and designing Year 11 and12 curricula since 2001. More importantly, it has been in this space that I have viewed the links between educational technologies and

- agile project management,

- SaaS services through courseware such as Articulate Storyline, Captivate, Learn Dash and Teachable and, most recently,

- team-focused digital platforms created by Atlassian, Hubspot and Kajabi.

What’s more, in 2017 I enrolled in a Masters course at Monash University with Professors Neil Selwyn and Michael Henderson. The course opened me up to key challenges in education technology.

Arriving At The First Principles Of Learning

How much of my career trajectory has been the result of a Knowledge Economy to which Professor Masters alludes in his keynote, or due to the challenges of my own circumstance would take more than this blog to explain.

Nonetheless, Professor Masters explanation of the first principles of learning challenges me now to ask what role a freelance curriculum content creator like me might play in urgently addressing the future organisation of schooling to reflect how

I know the importance of learning progressions in my existing curriculum projects. And as I review what that means against Professor Masters’ first principles, the curriculum creator in me knows I must navigate complex and competing demands from policymakers, community expectations and, most importantly, students need.

At the same time, I’m mindful that my career trajectory – from a teacher to textbook writer, self-funding curriculum experimenter and now freelance curriculum designer – is hardly the norm. However, could there be something of value in it that foreshadows the need to grow new and innovative curriculum content creation services for a Knowledge Economy?

Then, the principles of learning outlined my Professor Masters provide me with a seismic challenge to be “guided more by our emerging understandings of human learning than by education models of the past.” (Masters 2021, 4)

Footnotes

- Masters, G. (2021, August 16-20). How education gets in the way of learning [Keynote presentation]. Research Conference 2021: Excellent progress for every student: Proceedings and program. Australian Council for Educational Research

- ACER’s Learning Progression Explorer.

- Richard Pountney, SIG Lead, Sheffield Institute Of Education, Sheffield Hallam University, February 22, 2021, Researching Curriculum Subjects: understanding how teachers plan, design, and lead the curriculum, A presentation made as part of the BERA British Curriculum Forum