OK, I admit it! Using dramatic play in teaching is hard work! For instance, I know the hard work of completing the project on humour and thinking skills with Year 6 & 7 students, shown in the featured image, through letting students learn about the origins of the clown, Arlecchino.

So, why do it? Why not just stick to the common, everyday lesson plan formula?

For me, the answer lies in what’s missing. I’m troubled that for all their wisdom, the high-impact teaching strategies (HITS) often miss the mark on enabling students to know and experience being creative.

This brings me back to the contradiction I know to be dramatic play. How is it that something that starts as child’s play transforms into virtuosity—that troublesome and obsessive state that comes from hours of practice and attention to detail? I have spent my teaching life trying to imagine how literacy skills are part of that same journey.

Given the current focus on cognitive science and AI, this exploration is more vital than ever. So, for me dramatic play is part of ensuring foundational literacy skills along with my students’ sense of personal and social well-being.

What’s AI Got To Do With It?

I joined Curriculum Writers Association Australia from its foundation in 2023 because I believed it to be an important forum in which I could have on-going discussions about how technologies and policies impacted how I viewed myself as a curriculum writer. Since then, I’ve discovered it to be a robust organisation that looks at the many overlapping issues between individual and public ownership of education content creation. I admire its presentation of ’round-table’ discussions, along with its Scholars’ Circle (educators with doctorates) and AI Committee. I am currently a member of the Scholars’ Circle who are embarking on helping to draft CWAA’s manifesto.

Above all, CWAA signals the fact that technology has created a massive paradox for educators: on the one hand it has given them 24/4 access to information and tools for content creation (subject knowledge and other educational topics on steroids) while simultaneously risking the teacher’s and student’s human capacity to achieve ‘deep learning’. ‘Cognitive load’ and ‘cognitive offloading’ are now everyday terms.

Through following John Hattie’s work (e.g. Visible Learning and the Science of How We Learn, 2013) and educational historians like Professor Norm Friesen, I accept that these contradictions and controversies around ‘edtech’ have, at least, a twenty-five-year history. And although, difficult to easily summarise, the founding committee members of CWAA have set up the means for a public airing of issues under in a rapidly changing environment, not the least evident via theincorporation of AI into the classroom.

First Things First: What Progress Map Am I Focused On?

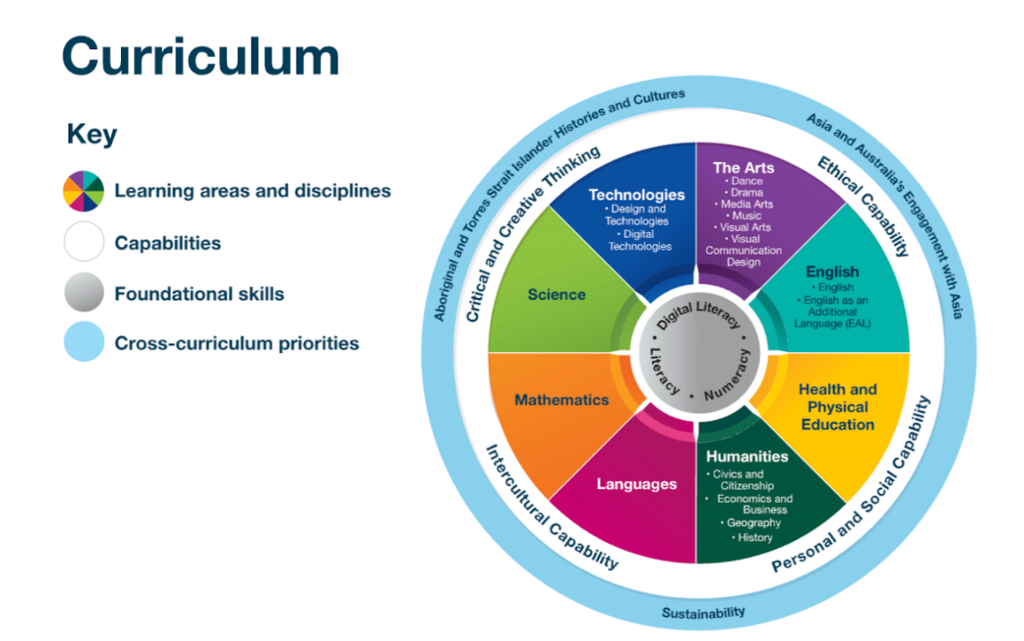

I’m sure that by now in Victoria we are all familiar with the fact that the Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority VTLM2.0 have named three Foundational skills: Literacy, Numeracy and Digital Literacy. These are “fundamental to learning across the curriculum” as they enable “learning for all students during their years at school”. The diagram below captures their centrality, which the VCAA directs us to meet through learning outcomes in English, Mathematics and Digital Technologies curricula.

Speaking specifically, let’s consider just one key aspect of Literacy emphasised in VTLM2.0, namely the importance of oral language. To turn that imperative into reality, the VCAA offers two excellent on-demand professional learning courses to help teachers understand phonic and word knowledge in relation to English Version 2.0, one course by Dr Emina McLean (focusing on the early years) and one by Professor Pamela Snow (dealing with adolescent learners).

Professor Snow’s work has lead the way in systematic approaches to literacy (as opposed to ‘whole language’ discovery approaches) for, at least, two decades. Her influence can be seen in publications such as Greta Rollo’s and Kellie Picker’s 2024 ACER report “Unpacking the science of reading research” which shows how oral language is “linked to semantic understanding, vocabulary, morphology and phonemic awareness”. The report highlights the development of phonological awareness on a continuum (p.12) using terms such as ‘syllable’, ‘rhyme’, ‘alliteration’, as well as verbs such as ‘blend’, ‘segment’ and ‘manipulate’. Together, the terms define content for the phonetic foundation of oral and written language.

As a teacher viewing the continuum, I’m cognisant of the amount of practice a child needs to meaningful acquire phonological awareness. Furthermore, I have experienced how a child’s motivation is tied up with the meaningful achievement of becoming a successful communicator.

Matching knowledge, practice and experience

The challenge of turning pedagogical knowledge into meaningful practice for students is not new. It was a puzzle we were tackling as educators back in 1998, for instance, when curriculum leaders discussed the cartoon of ‘teaching dogs to whistle’. At the time, I worked for the Education Department of Western Australia as a curriculum officer, implementing the reform to outcomes-based education. The concept of ‘essential content’ was pivotal to understanding what was at play in the workshops, where ‘essential’ had to measure up to teaching content meaningfully.

Impact of the ‘memory paradox’

Today, cognitive science provides us with a new and powerful language to understand ‘meaningful’ learning. We can better understand our students’ need for frequent exposure and practice of essential oral language skills. Consider how in “The Memory Paradox: Why Our Brains Need Knowledge in an Age of AI” (May, 2025), Barbara Oakley, Michael Johnston, Ken-Zen Chen, Eulho Jung, and Terrence Sejnowski show how closely teaching and learning must be coupled.

The article as a whole acts as a warning to counteract the cognitive ‘offloading’ made possible by technological communication and productivity tools, now exponentially enhanced by AI. Focusing on the intertwined processes of declarative and procedural memory systems, the main message presented by the five authors is the importance of the Memory Consolidation Processes that requires the use of the brain’s two memory systems: namely, how the two systems show that “deep learning is a matter of training the brain as much as informing the brain.” (p. 15).

Perhaps most interest of all are their observations on how “Reinforcement Principles” used in training AI thinking has come to illuminate human memory formation. In fact, the AI models our brains need for structured practice and repetition to build and strengthen neural pathways. Unstructured “discovery” simply isn’t as effective. This is because,

T[t]his convergence between human memory and artificial learning systems reveals a profound insight: prediction errors drive learning across both domains. This parallel explains why knowledge internalized in memory enables far more efficient learning than constant cognitive offloading to external devices. When we consistently outsource thinking to technology, we effectively bypass our brain’s natural reinforcement learning mechanisms—the very pathways that build and strengthen neural manifolds supporting sophisticated thinking.

Exploring dramatic play for learning effectively

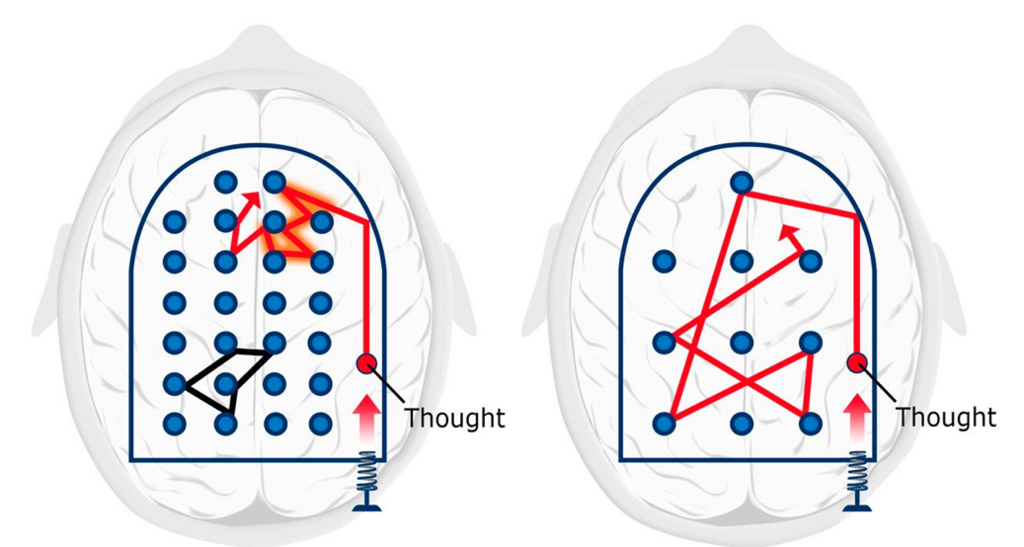

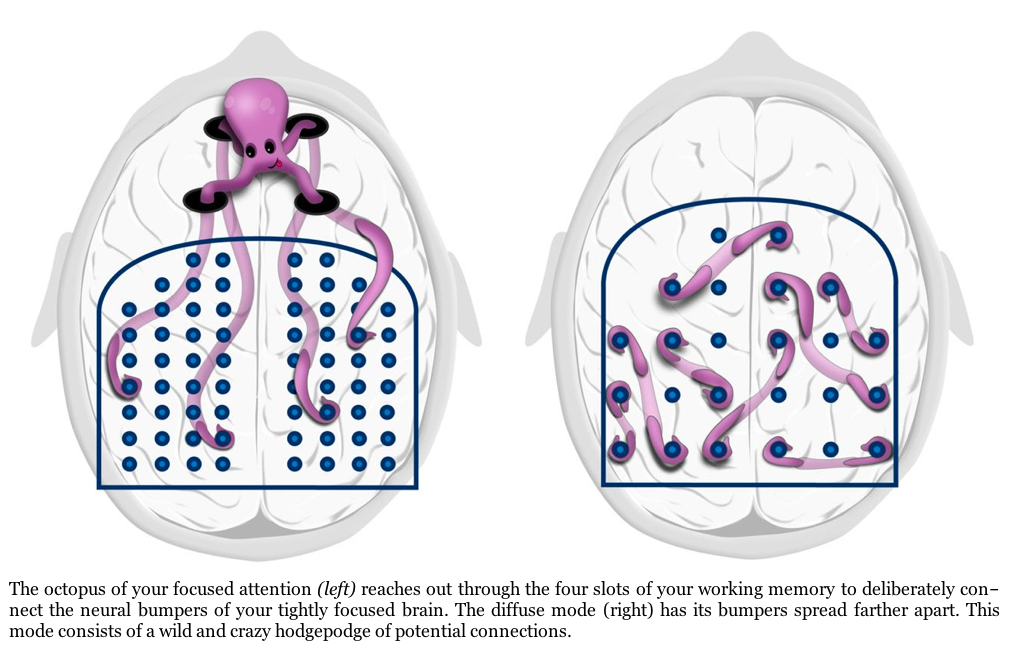

I’ve followed Oakley’s and Sejnowski’s teaching of cognitive science since 2016 when I completed their Coursera MOOC Learning How to Learn: Powerful mental tools to help you master tough subjects. The course uses an analogy of the brain ‘as a pinball machine’ to explain the two modes of thinking which neuroscientists attribute to learning, the focused and diffuse mode. In fact, the whole learning experience is presented as playfully dramaturgical. I interacted with ‘the zombie within’, playing pinball, building good walls over time, having an octopus of attention, solving a jigsaw puzzle and changing the legs of octopi into ribbons to transport ‘chunks of knowledge’. All this, to teach the deep connections between long-term and working memory.

My journey into cognitive science, however, didn’t start with MOOCs. It began in 2002 through a movement in my own field: the ‘cognitive turn’ in theatre history, through which I viewed partnerships between theatre historians and cognitive philosophers and linguists such as George Lakoff and Mark Johnson. Consequently, theatre historians at the tertiary level began to explore the cognitive and evolutionary foundations of performance. For instance, Bruce McConachie and Elizabeth Hart edited Performance & Cognition (2006), a collection of essays, exploring abilities like perception, memory, imagination, and empathy, and their evolutionary roots.

What Changes With A ‘Cognitive Turn’?

The ‘cognitive turn’ in my drama teaching really took off even further in 2005 when I explored how the drama elements enabled students to use oral language in playmaking projects. These were after-school and school holiday ‘nonsense projects’ for upper primary to lower secondary students, (Years 6 to 9) featuring a team of teacher-artists: including a choreographer, an animator, filmmaker, playwright and philosopher. Schools were able to view the content of the programmes and join the playmaking approach in a festival for young playwrights.

The project was wildly ambitious and impossible to sustain financially. Nonetheless, it did allow me to explore the complex pedagogy of how ‘the playwright’ exemplified a multimodal creative process which moved from oral language skills to creative writing.

Dramatic play as a rich rehearsal space

So, where does my exploration of cognitive science, memory, and virtuosity lead me in the practical world of the classroom? It leads me back to a crucial question: how can dramatic play augment the explicit, research-backed literacy instruction that my students need?

This is about deeply understanding the aims of systematic phonics programs (SSPs) like Carol A. Christensen’s Reading Links, used by the literacy team in which I worked in my school. Hence, I bring my expertise in drama education to see oral language as a powerful junction point where three distinct pathways converge:

- The technical path of voice production and speech articulation based on phonological awareness.

- Acquiring vocabulary and grammar in metacognitive meaning making activities.

- The emotional path that governs a student’s confidence and well-being.

For older students struggling with decoding, that emotional path is often blocked by what Professor Snow identifies as shame. To clear that blockage, we can’t simply drill the technical skills harder. We must create an experience that integrates all three pathways.

Continuing to affirm creativity

So, in my next blog, I want look in more detail on how drama and literacy seem to have a ‘natural’ relationship, yet drama remains an ‘elective’, outside foundational literacy skills. At best, it is part of the English curriculum and its literary history. Interestingly, the same history has an interesting line events around the evolution of the English language as vocabularies and accents became the subject of ‘enunciation’ and ‘received pronunciation’.

The emergence of drama education in school curricula internationally speaks to other developments in education with regards to the positioning of creative learning and aesthetic education . This approach is a direct application of what the arts educator Maxine Greene describes in Variations On A Blue Guitar, that students are required to be fully present in the work. As Greene herself wrote:

“…if the painting or the dance performance or the play is to exist as an aesthetic object or event for you, it has to be attended to in a particular way. You have to be fully present to it… you have to be there in your personhood, encountering the work much in the way you encounter other persons.”

This state of being “fully present” is the ultimate goal. It is the antidote to the cognitive offloading we discussed earlier; it is the very essence of the deep learning that builds strong neural pathways from decoding to fully comprehending what you read as a literate person.

Estimated reading time: 10 minutes